Welcome back to Venture Logbook. This is our year-end edition, and the final newsletter of 2025.

To wrap up the year, we’re using one report to zoom out and see what actually happened in AI over the last 12 months:

State of AI: An Empirical 100 Trillion Token Study with OpenRouter was released by a16z x OpenRouter. It analyzes real-world AI usage patterns across 100+ trillion tokens, 300+ models, and 60+ providers, spanning Nov 2024–Nov 2025.

One quick note before we dive in: everything here is based on OpenRouter’s data and report. OpenRouter is a model routing and aggregation platform, so this isn’t the full picture of the market.

Still, the sample size is huge, and it’s a pretty solid signal. Let’s break it down.

The Tokens Tell a Different Story

The Surprise Winner in Open Source: Roleplay

In open source model usage, Roleplay takes more than 50% of the share. And within Roleplay, Games and RPGs make up around 60%.

Programming is still the second-largest category, but in open source it’s much smaller than most people would guess, roughly 15–20%. Here’s the twist though. In paid models, programming jumps dramatically, sometimes over 50%.

This is why the usual market narrative feels a bit incomplete. We keep hearing “AI = productivity,” and that’s true, but the productivity demand is heavily concentrated in the higher-end models people are willing to pay for, like Claude 3.5 Sonnet. Meanwhile, open source becomes the default home for entertainment and creative play.

Another way to read this is simple. People will pay for output quality when it affects work. But for fun, creativity, and roleplay, most people don’t feel the need to pay more when open source is already “good enough.”

Open Source Is Not a Toy Market Anymore

According to the OpenRouter report, Chinese open source models jumped from about 1.2% of global usage in late 2024 to nearly 30% by mid-2025. That alone forces a rethink of the old assumption that closed models are always “better” and open source is just for demos.

The open source scene also moved from one clear winner to a crowded battlefield. DeepSeek is still strong, and in some cuts it accounts for 50%+ of open source tokens, but it’s no longer a single-player market. Models like Qwen (Alibaba), MiniMax, and Kimi (Moonshot AI) are all fighting for share.

The most interesting part shows up in programming. Developer loyalty to any single open source model is basically close to zero. It’s purely rolling evaluation, whoever performs best right now gets picked right now.

Open source coding assistants have become extremely dynamic. Qwen2.5 Coder 32B helped create a real category after its Nov 2024 release. Before that, this segment almost didn’t exist. Now Mistral Small 3 and GPT-OSS 20B are finding PMF in the same zone.

And the direction is clear. Users are no longer blindly chasing “bigger is better.” They’re hunting for the cost-performance sweet spot. Models around ~32B often hit the best balance between capability and cost. They’re not underpowered like smaller models (<15B), and they’re not painfully expensive and slow like ultra-large ones (>70B) with heavier inference and infrastructure costs.

So yes, open source is still messy and fast-moving. But that’s exactly why it’s worth watching. It’s a huge market, it’s getting better quickly, and the “final winner” is nowhere near decided.

From Chatbot to Agent Is Already Happening

Late this year, the “AI bubble” conversation got loud. And agents became an easy target. If AGI isn’t coming soon, people assume agents must be overhyped too, like they were only valuable as a shortcut to AGI.

But the OpenRouter report points in the opposite direction. What we’re seeing is not agent hype fading. It’s inference shifting.

Reasoning-optimized models went from basically zero share in early 2025 to 50%+ of tokens by year-end. Models are not just predicting the next word anymore. They are doing multi-step thinking, internal planning, and refinement.

The report also looks at requests where finish_reason is tool_calls. That metric matters because it captures a real behavior change. AI is moving from “chat” to “do”.

In developer workflows, the model is no longer a single-pass chatbot response. It’s agentic inference. Multi-step planning, tool calls, iteration, retrying, and self-correction. That’s the actual turning point from chatbot to agent.

You can see the shift in the raw usage patterns too:

- Average prompt length grew from about 1.5K tokens in late 2023 to 6K+ by late 2025, roughly 4x.

- Average completion length went from about 150 to 400, about 3x.

- Coding prompts are in their own universe, often 3–4x longer than other categories, and frequently over 20K tokens.

This is what “from Q&A to task execution” looks like. It also means context windows are no longer a nice-to-have. They’re core infrastructure.

The report makes another point I fully agree with. Tool use is no longer an advanced feature. It’s becoming the baseline. Future evals cannot just test whether the model answers correctly. They have to test whether it can reliably use a toolchain to complete a task.

So the competitive axis is changing. We’re moving from pure “IQ” metrics, accuracy and benchmark scores, toward “execution” metrics. Reliable tool calling. Staying attentive across long contexts. Actually finishing the job.

Honestly, it’s the same split we use for humans. Being book-smart is real. But in real life and real products, execution is what users feel. If you’re building for science or research, you might care more about raw intelligence. If you’re building for productivity, you care whether the system can complete tasks, end to end, with tools.

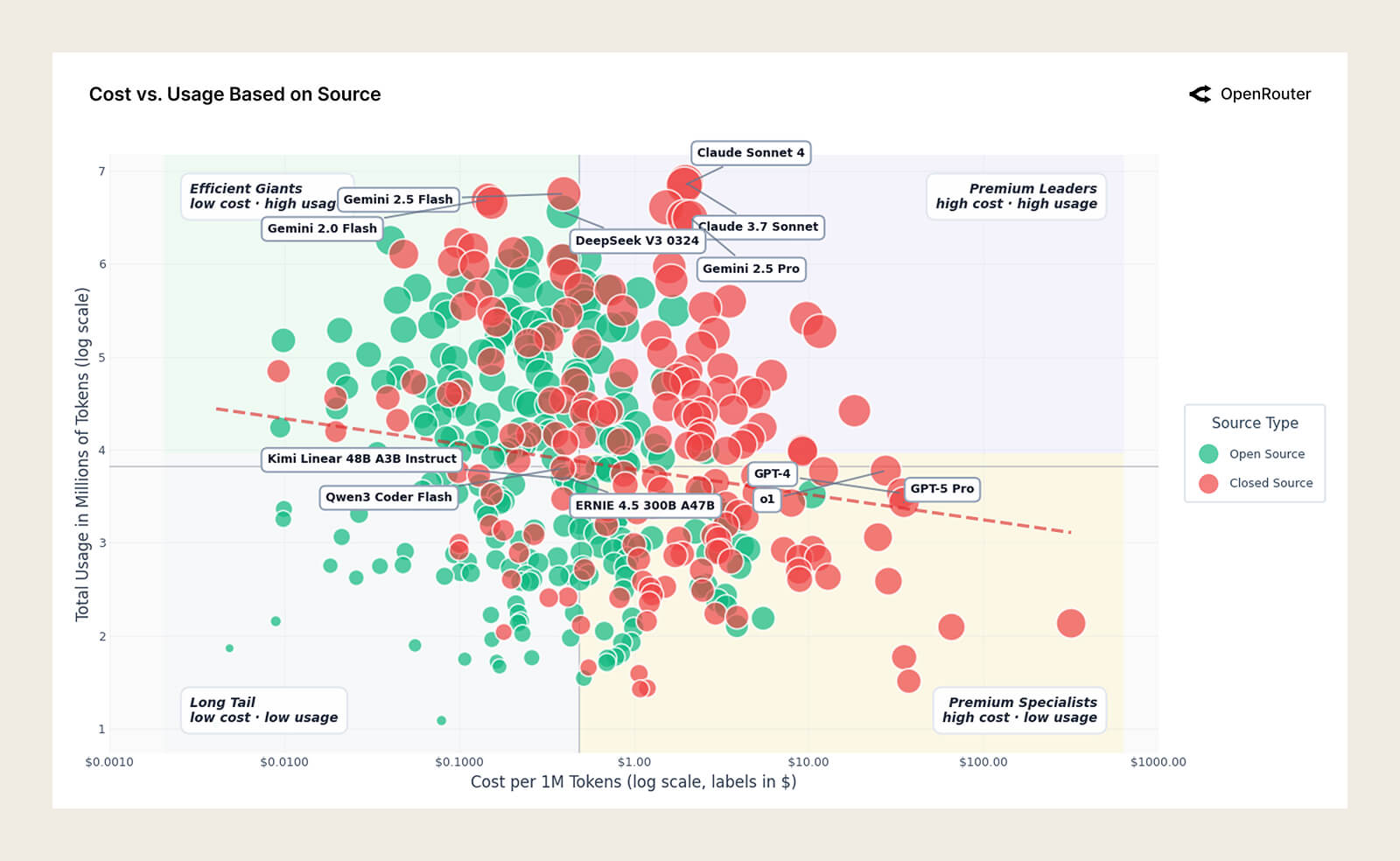

The Counterintuitive Complexity of Cost

If you’re building on the application side, it’s useful. If you’re on the foundation model side, it’s even more useful. It’s basically a map of what the market is paying for, and why.

The Landscape

At the top is Premium, and it’s dominated by tech. That makes sense. When a model helps solve genuinely hard technical problems, the value of solving the problem is way bigger than the API bill. In that tier, the competition isn’t “who’s cheapest.” It’s “who can actually solve the hard thing.”

Then there’s Specialized, the high price, low volume zone. Think finance, health, legal. These categories don’t run at programming-level frequency, but they can still justify premium pricing because the stakes are high. The real fight here is accuracy and trust. And “accuracy” isn’t just about getting the right answer. It also includes whether the model can hold the full context without dropping details. This is part of why Gemini’s huge context window made such a splash when it came out. It changed what “reliable” could mean in workflows that used to rely heavily on RAG and retrieval tricks just to stay grounded. In these domains, a small error doesn’t just look bad. It can become real risk and real cost.

The last tier is Mass Market, low price and high volume. Programming shows up here, and that’s the interesting part. It overlaps with Premium in a very real way. In developer tools, you can feel this split. A lot of “secret” models get tested privately on exactly this question: can you push a lot of context through it without the bill exploding, and does it stay good enough?

And from my own coding habits, this is exactly how it plays out. If it’s something a junior dev could handle, I’ll happily use a mass-market model. But if it’s architecture-level thinking, or a bug I’ve been stuck on for a week, I’m going straight to Premium. That’s why price matters more inside mass market, and matters less at the top.

Weak Price Elasticity

AI Still Isn’t a Commodity

This ties directly to the landscape above. The report shows price elasticity is weak. A 10% price cut only increases usage by around 0.5–0.7%. That is not what a commodity market looks like.

Right now, especially for enterprise and serious developer workflows, “does it work well and does it stay stable” beats “is it a bit cheaper.” Once a workflow is running, a discount usually doesn’t convince people to switch. Switching models isn’t shopping. It’s migration. And migration only happens when there’s a real step-change, not a small price delta.

Jevons Paradox

The report observes this Jevons Paradox effect in the “efficient giants” group, models like Gemini Flash and DeepSeek. Once the cost drops and throughput goes up, usage becomes more aggressive: people throw in the entire codebase, run multiple rounds of reflection, or generate ten options and pick the best one.

So even if the price per token drops by 90%, total usage can explode. The report cites cases where token count jumps by 1000%. The result is counterintuitive but real. Lower unit cost can lead to higher total spend, because the workflow becomes more “luxury” in how much context and iteration it consumes.

Cinderella Glass Slipper Effect

When a model is the first to solve a workload that used to be painful or impossible, the right users lock in hard. That’s the Cinderella glass slipper moment. It fits perfectly, and everything else feels “off.”

If a new release hits an unmet technical constraint or a cost constraint, it creates strong lock-in fast. Once teams build workflows, pipelines, and habits around a model, switching becomes expensive. This is why “first to solve it” can matter more than “eventually the best.”

My take: this looks like a new kind of PMF. Not product-market fit, but workload-model fit, or more precisely workflow-model fit. Across both enterprise teams and developers, most people are still experimenting. The market is not settled. But when the fit happens, it hardens quickly.

You can see this clearly in the Claude coding stack. In a lot of Silicon Valley teams, adoption is bottom-up. Developers push internally for Claude-class coding models to be the default inside tools like Copilot, Cursor, or whatever wrapper they use. That’s not just preference. That’s trust, and it’s a workflow anchored around a specific model family.

Boomerang Effect: DeepSeek Users Leaving, Then Coming Back

The report describes a “boomerang” pattern for DeepSeek. Some users churned early, then returned 2–3 months later. The likely reason is simple. They tested alternatives and still found DeepSeek best for their specific tasks. This is the underrated defense in a chaotic market. A distinct cost-performance edge or a narrow domain strength can pull users back even after they roam.

Launch Window: You Only Get One Shot at Lock-In

Different models have very different retention trajectories. Some cohorts stick. Others spike and collapse.

The core idea is the launch window. You have a short window to establish workload-model fit. If you miss it, even a later model with similar performance may not get adopted, because the workflow is already spoken for.

This moat is not brand-driven. It’s migration-driven. It looks a lot like the old cloud server story, and honestly like databases too. Once you’re on AWS or once you’ve standardized on Oracle, moving is rarely “just switching vendors.” It’s a high-friction, high-risk migration.

My take: this is getting harder for everyone, open or closed. If a model release doesn’t come with a clear unique recipe and a sharp, specific advantage for a specific workflow, it’s tough to earn lock-in. Teams will test fast, compare against alternatives, and move on if the fit isn’t obvious. That puts real pressure on model development strategy.

It’s no longer just “iterate more.” It’s “iterate toward a distinct capability that a real workload actually needs.”

Fast iteration can still work if you treat it like trying on shoes until one truly fits. But there’s a cost. Constant shoe-changing creates fatigue. That’s why the real work has to happen before launch. Not just private tests to climb benchmarks, but private tests that answer one question: which workflow problem does this model solve better than anything else right now?

So What Actually Matters Now?

Roleplay Is Underrated

Roleplay is clearly underappreciated as a demand category. But it’s also undervalued in the “go-to-market” sense. People default to whatever is already installed. If someone is roleplaying today, they’re often doing it inside a giant consumer app like ChatGPT or Grok.

That’s hard to beat, not because startups can’t build a better roleplay experience, but because these apps compound context. They have more user history, more memory, and more daily touchpoints. Over time, that personalization becomes a moat.

If a startup wants to win here, I wouldn’t try to out-generalize the generalists. I’d localize. Small languages, specific cultures, specific fandoms. Or go creatively vertical, like an animation-first roleplay product where the output format is the differentiator, not just the chat.

China’s Open Source

Chinese open source models are shipping at a near-monthly cadence, and each release tends to be aggressively priced while staying competitive with, and sometimes surpassing, closed models on real usage. That pace plus price pressure is an unfair advantage in distribution and mindshare.

The West’s closed-model moat is increasingly not “we’re always better.” It’s three things: First, consistency. Open source quality can swing more between versions and checkpoints. Second, ecosystem. Closed models win by integrating cleanly into existing software stacks, Salesforce, Shopify, and the rest of the enterprise plumbing. Third, trust. Enterprises are cautious about models trained on unknown, messy, or politically controversial data sources, especially in regulated environments.

So the market is splitting. Open source keeps gaining on speed and cost-performance. Closed models defend with stability, integration, and enterprise trust.

Workload-Model Fit Is the New Aha Moment

The old playbook was “ship fast, iterate, and you’ll find it.” Model launches don’t work like that anymore.

Retention now is brutally tied to whether you solve a real job-to-be-done at launch. You need the Cinderella moment first. The moment where a specific workflow finally clicks, and teams build pipelines and habits around your model. Once that happens, switching becomes migration, and migration is expensive.

Benchmarks still matter, but they’re secondary. They’re not the aha. The aha is solving a real task so well that the workflow locks in. That’s what creates durable retention in a market where everything else is getting cheaper, faster, and easier to test.

In this game, Workload-Model Fit is the new moat.